The likelihood ratio combines both sensitivity and specificity and tells us how likely a given test result is in people with the condition, compared with how likely it is in people without the condition.

In the example, we used the Lachman test, which is one of the most accurate tests that is out there in clinical practice. However, let’s look at a different, less accurate test like the Thessaly test and how our example plays out there:

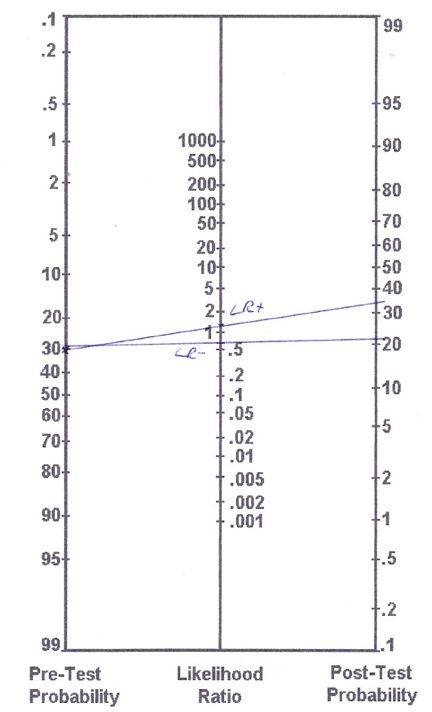

According to Goossens et al. (2015) the Thessaly test has a sensitivity of 64% and a specificity of 53%, which results in a LR+ of 1,36 and a LR- of 0,68. As you can already see, these values are pretty close to LR = 1, which tells us that they will change the probability that a person has a meniscus lesion very little. To apply these values to our example of our ACL tear case, we know that ACL tears are often accompanied by meniscal tears. Although our patient does not report about any locking or catching sensations, we estimate our pre-test probability at about 30%.

Our nomogram looks like this:

Based on the (more accurate) calculations we end up with the following post-test probabilities:

– Pre-test odds: Prevalence/(1-prevalence) = 0,3/(1-0,3) = 0,43

– Post-test odds (LR+): 0,43 x 1,36 = 0,58

– Post-test probability (LR+): post-test odds / (post-test odds+1) = 0,58/(0,58+1) = 0,37 (so 37%)

– Post-test odds (LR-): 0,43 x 0,68 = 0,29

– Post-test probability (LR-): post-test odds / (post-test odds+1) = 0,29/ (0,29+1) = 0,22 (22%)

So with a positive Thessaly test, you have increased your chances of a meniscal lesion from assumed 30% to 37% and with a negative Thessaly test you have decreased your chances to 22%.

So like you can see from this example, the outcome of a test with little accuracy will not influence the likelihood of the presence or the absence of a certain pathology very much.

If you want to perform multiple tests, say you want to add the Anterior Drawer test in our ACL example, you will base your pre-test probability on the post-test probability of the Lachman test. So in case of a positive Lachman, you will start with a pre-test probability of 95% and with a negative Lachman you will start with a pre-test probability of 19%.

While most tests either have a positive or negative outcome, there are also test clusters with multiple outcomes. So, if you take the cluster of Laslett for example, for 2 out of 5 positive tests you will end up at a LR+ of 2.7, for 3/5 at a LR+ of 4.3 etc.

Be aware though, that with a very high pre-test probability, adding another test has little value and it is better to start your treatment. The same is true for a very low pre-test probability in which case you don´t test and also do not treat the condition.

As an example, if a patient presents to you with sudden onset of low back pain, neurological symptoms in both legs, problems with micturition and saddle anesthesia, you would be pretty sure that this patient has cauda equina syndrome, which is a red flag and requires urgent surgery. If you are say 99% sure of your diagnosis, a straight leg test (SLR) with a LR- of 0.2 will decrease the post-test probability to 95%, which is still very high and you would still want to send this patient for surgery.

In turn, if the test was positive, you would probably go from 99% to 100% certainty, so why bother testing in the first place, especially if this is an urgent referral for surgery?

The same is true for a very low pre-test probability. If a patient presents to you without radiating pain below the knee, the chance of this patient for radicular syndrome due a disc herniation is very low, say we assume 5%. What would happen in this case if you performed the SLR with a LR+ of 0.2? You would end up at a post-test probability of 10% and if the test was negative the post-test probability would have decreased to maybe 4%. If you are almost certain, that a patient does not have a certain disease, why test it in the first place?

Of course, in practice the decision to do a certain test always depends on various factors such as costs, severity of a disease, risks of the test etc.

If you are interested in further reading, we can recommend you to read the following article, from which a lot of our text from above is derived:

Davidson et al. (2002) – The interpretation of diagnostic test: a primer for physiotherapists.